Will the US Debt Crisis Crash Global Markets?

Key Points

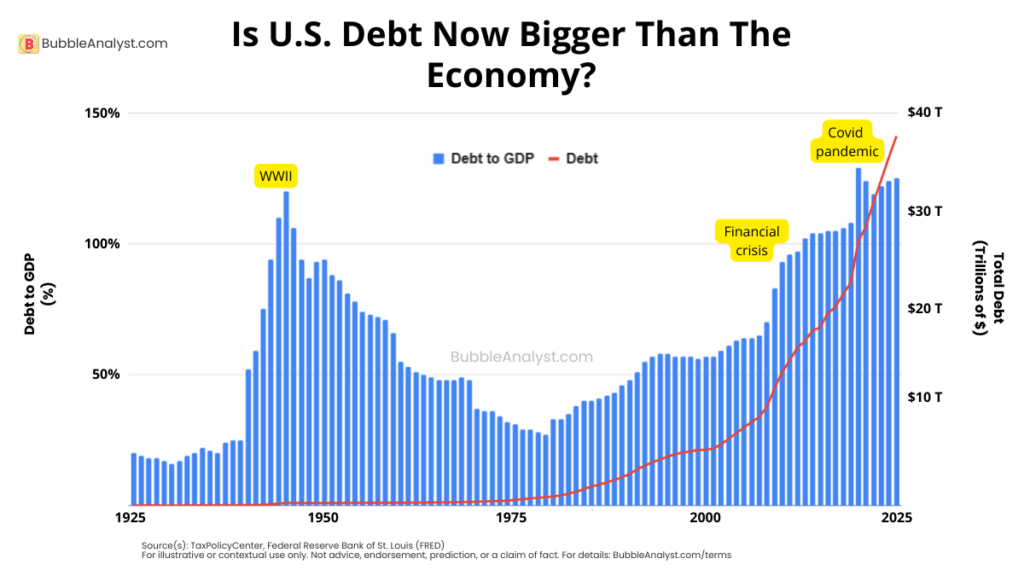

- U.S. debt has surged from roughly $10T to nearly $40T in under two decades—pushing gross debt above 120% of GDP, a level last seen only around the post–World War II crisis.

- The U.S. holds nearly 35% of ‘global’ government debt, and with interest payments now rivaling the defense budget while deficits remain persistent, this represents an unprecedented debt situation in American history.

- Absent a debt reset or similarly drastic intervention, the risk of a first-ever U.S. sovereign breakdown—unthinkable until recently—moves from theory toward possibility.

How debt grew

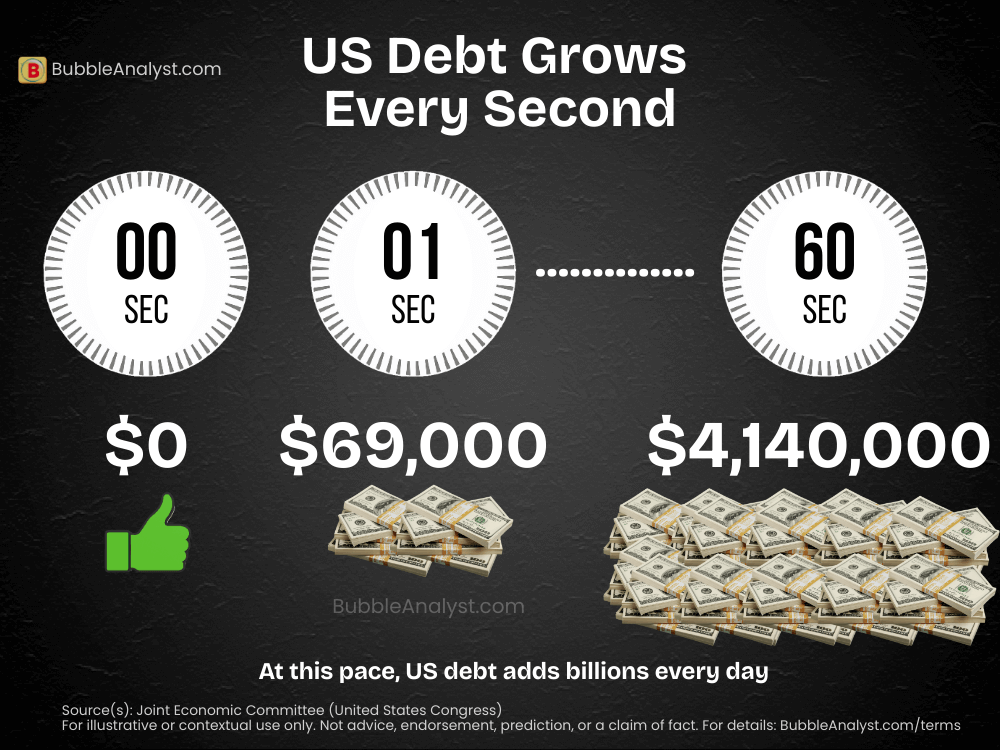

By the time you finish reading this article, U.S. national debt will have grown by tens of millions of dollars. What we are witnessing today is not just rising numbers, but a full-scale US debt crisis taking shape in real time. The Joint Economic Committee estimates it’s currently rising at about $69,000 – every single SECOND.

That’s nearly one full year of a person’s salary added to the national debt — every ‘second’. As of 2025, U.S. federal debt has crossed $38 trillion, pushing the debt-to-GDP ratio beyond 120% — a level historically linked to deep fiscal stress across economies. This pace of borrowing is what turns high debt into a full-blown US debt crisis. This is the debt crisis reshaping the macro outlook, and one that could plausibly trigger the next US recession. Here’s why the risk is no longer theoretical.

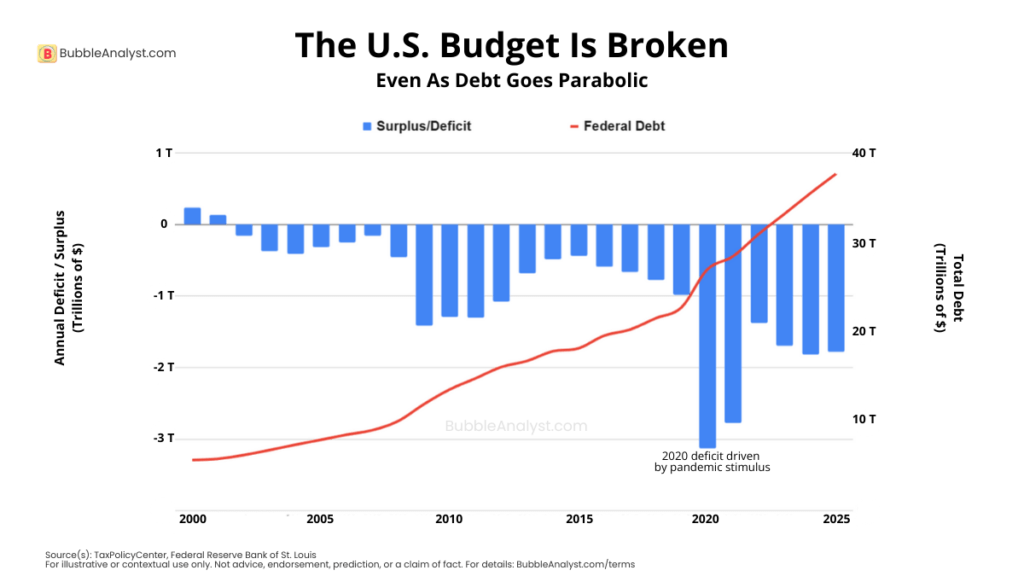

In the year 2000, the total U.S. federal debt stood at roughly $5.7 trillion, with a debt-to-GDP ratio of about 55%. At that time, America was running budget surpluses, the dot-com boom was in full swing, and confidence in long-term fiscal stability was relatively high. Fast-forward to today, and the picture looks dramatically different. U.S. federal debt has crossed $38 trillion, pushing the debt-to-GDP ratio beyond 125%.

This acceleration marks the shift from normal deficit spending to an outright American debt crisis—one that increasingly suggests some form of US debt reset may no longer be optional, but inevitable.

2008 Financial Crisis: The Turning Point in the US Debt Crisis

The turning point came during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. To prevent a total collapse of the banking system and economy, the U.S. government injected trillions through bank bailouts, stimulus packages, and emergency lending programs.

At the same time, tax revenues crashed due to mass unemployment and business failures. Between 2008 and 2012 alone, U.S. debt nearly doubled, fundamentally changing America’s fiscal trajectory.

Since then, every major shock — COVID, wars, inflation control — has been financed largely through fresh borrowing, turning debt from a temporary emergency tool into a permanent economic crutch.

U.S. Debt vs Global Government Debt

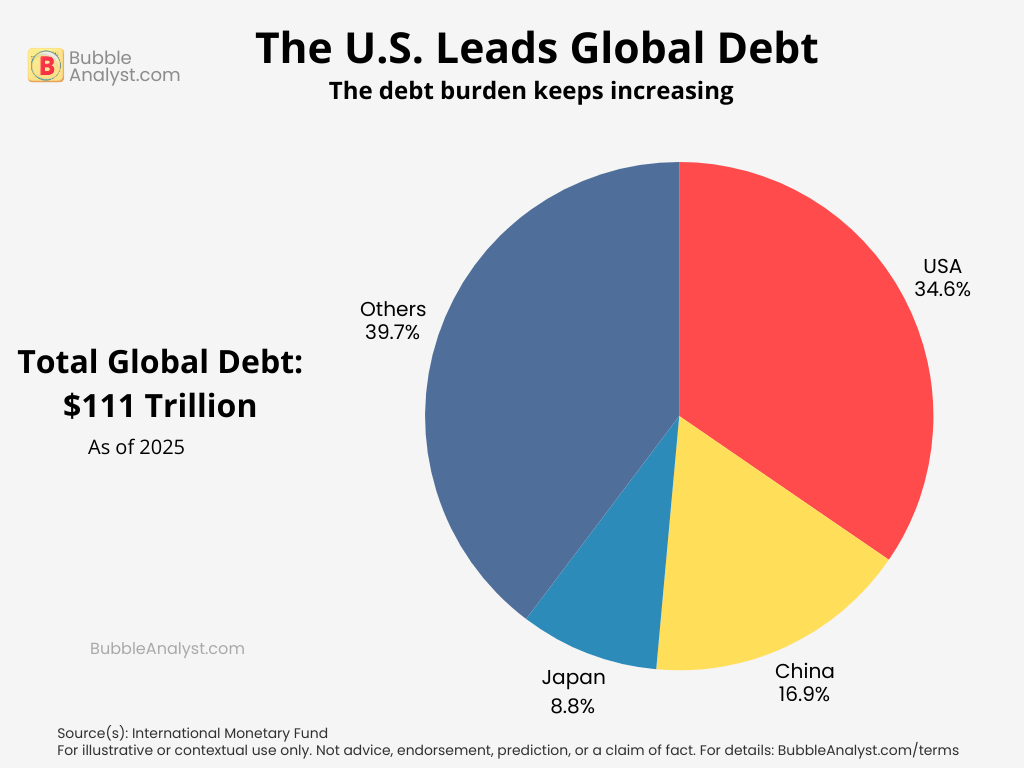

The United States holds the largest single share of global government debt. Of the roughly $111 trillion in total worldwide sovereign debt, the U.S. alone accounts for 34.5%, or about $38.3 trillion.

China ranks second, carrying 16.8%, roughly $18.7 trillion, while Japan stands third with 8.9%, or approximately $9.8 trillion.

Combined, the U.S. and China represent more than half (51.8%) of the world’s total government debt—highlighting how concentrated global sovereign risk has become.

Who owns the U.S. debt?

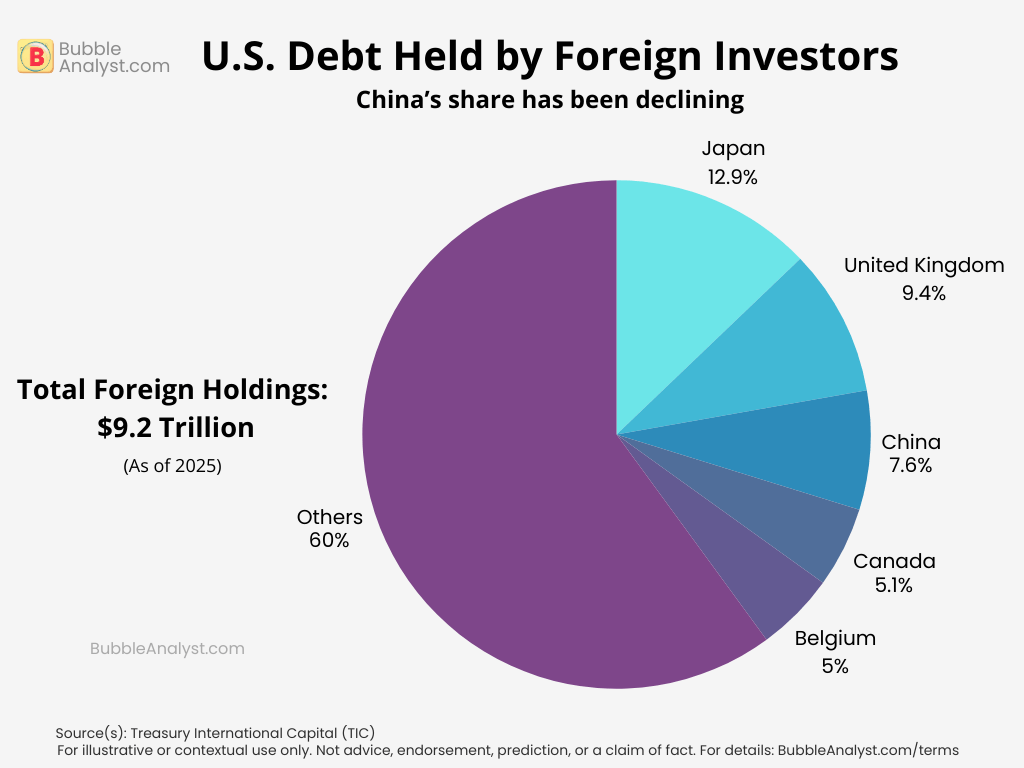

U.S. debt is more diversified than most people think. Of the total federal debt, about $29T is held by the public and $7T is owed to government trust funds like Social Security and federal retiree plans, as per The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Within the public slice, U.S. investors (households, banks, mutual funds, pensions, insurers) and the Federal Reserve are the biggest owners. The Journalist’s Resource states that the Fed alone holds around $4.5–5T in Treasuries.

Foreign investors own about 30% of publicly held debt (roughly $9T+), led by Japan (~$1.2T), China (~$0.7T), and the U.K. (~$0.9T).

Is Debt Too High?

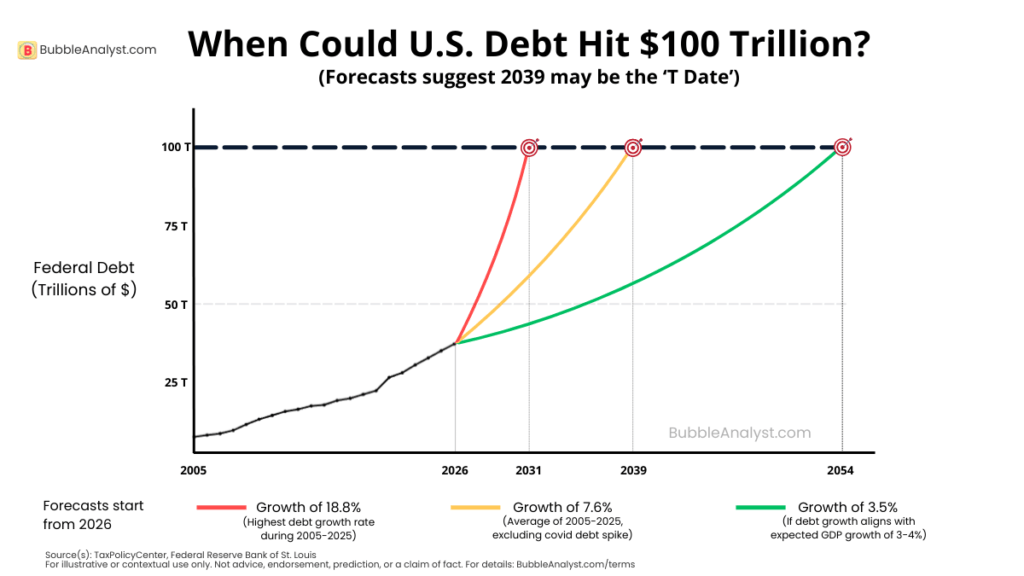

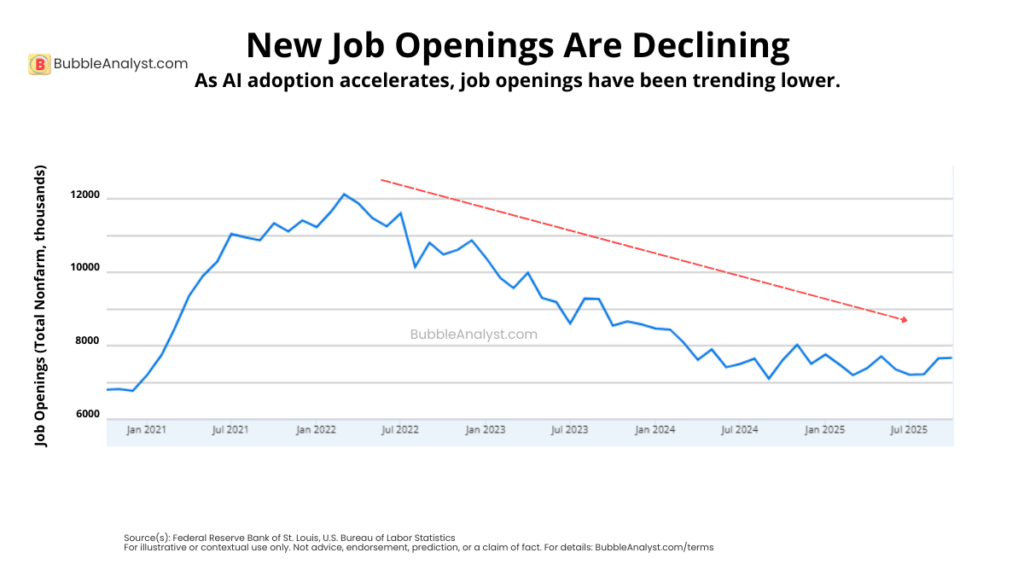

Here’s the simple picture: in recent years, U.S. debt has grown about 7% annually while the economy has grown around 3%. Run those lines forward and the math gets ugly: by the mid-2030s, debt could approach ~200% of GDP if the spread persists. Looking ahead, the real danger isn’t a slowdown in debt growth—it’s an acceleration. A major recession within the next 5–10 years isn’t a fringe outcome.

And when recessions hit, deficits widen, tax revenues fall, and borrowing spikes. If U.S. federal debt keeps rising at its historical ~7.5% annual pace, it crosses $100 trillion around 2039.

Now, some analysts point out Japan’s debt, which is about 230% of GDP and they’re doing ‘just fine’. True—but Japan is a different beast. Roughly 90% of its debt is held ‘domestically’. Households are net savers. It often runs current-account surpluses. And with an aging population, demand stays soft. Japan’s problem is deflation, not inflation.

Now let’s talk about the U.S. – and the picture is pretty much the opposite. A meaningful slice of Treasury debt sits with foreign holders such as China, Japan, and global funds. The population is younger and more consumption-driven. Trade deficits are persistent. And when the Fed opens the taps, i.e. prints the money for monetary easing, it shows up fast at the grocery store.

If these trends continue, the United States debt crisis moves from a fiscal concern to a systemic threat to markets.

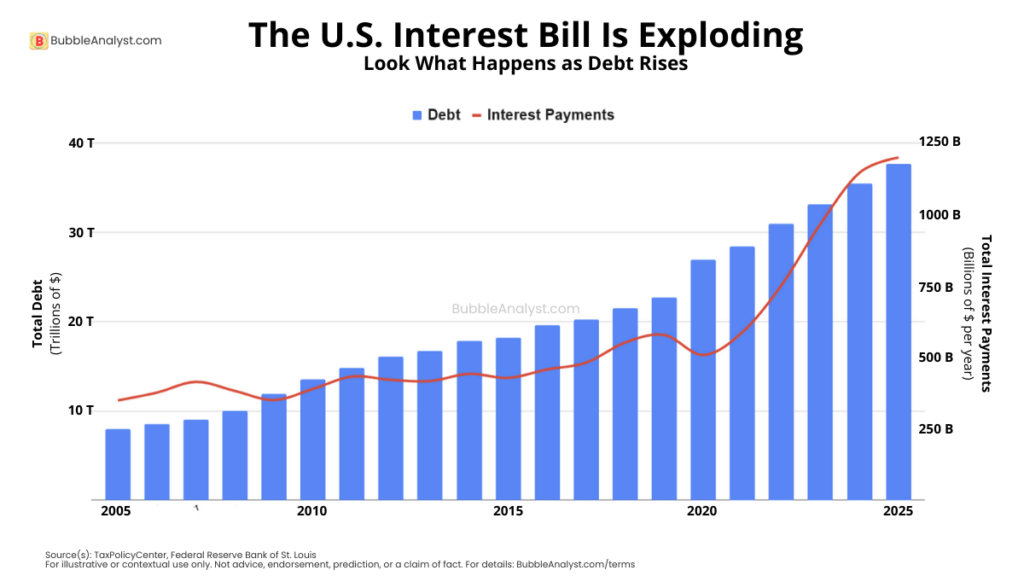

Interest Expense: The real reason behind the US debt crisis

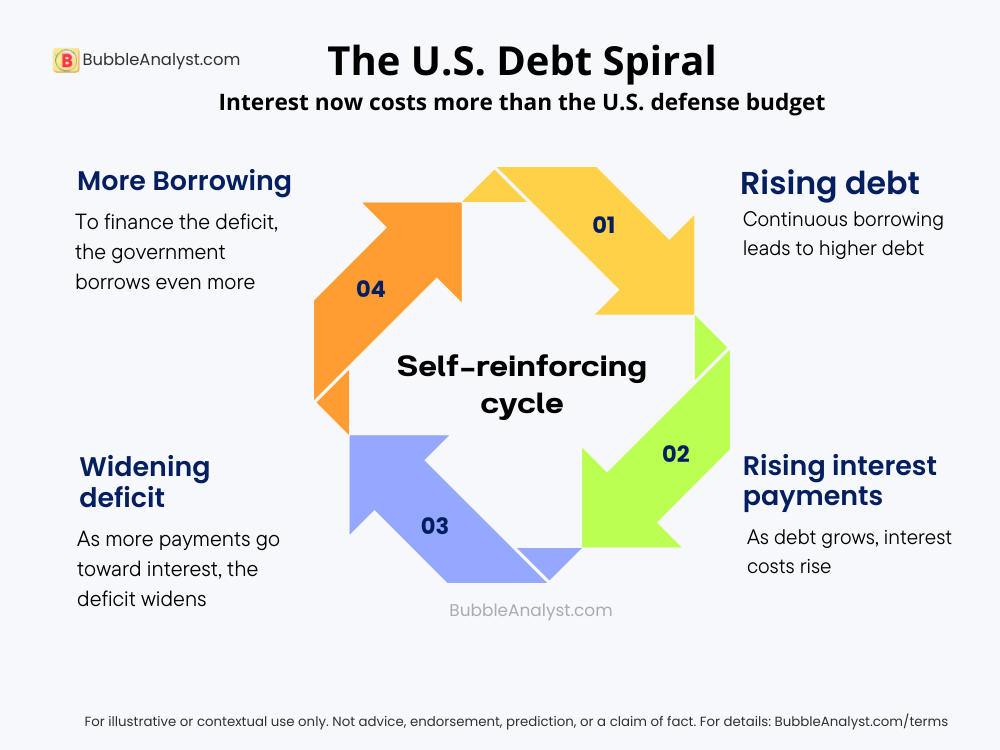

The US debt crisis is best understood visually. Over the past two decades, deficits have become structural, not cyclical, pushing total debt higher regardless of economic conditions. More troubling is interest expense, which is now accelerating as debt grows and rates normalize.

This creates a compounding trap: rising debt increases interest costs, higher interest widens deficits, and larger deficits require even more borrowing—often at higher rates.

Debt sustainability is not about one bad year—it’s about compounding. Once interest dominates the budget, flexibility disappears. Debt stops being a tool and becomes the system.

What could go wrong:

U.S. may go bankrupt

The U.S. has never gone formally “bankrupt” in its history. The closest we’ve seen are technical defaults and broken promises—like 1933, when the government refused to redeem dollars for gold, or brief debt-ceiling scares where payments were delayed.

But imagine a scenario where markets treat the U.S. as effectively bankrupt: investors lose confidence that Washington can or will fully honor its obligations. The first shock would hit foreign holders of U.S. debt—countries like China, Japan, and global central banks. They could demand immediate clarity or accelerated repayment, or start dumping Treasuries, sending bond prices crashing and yields spiking.

In response, a cornered U.S. government might publicly declare that it will protect its own citizens first: prioritizing Social Security, Medicare, military salaries, and pension funds heavily invested in Treasuries, while quietly restructuring or delaying some payments to foreign creditors. That kind of “America first” default would trigger a global financial earthquake: a rush out of the dollar, panic in bond and stock markets, chaos in global trade, and deep recession—if not outright depression—around the world.

Huge Recession

In a true “U.S. bankruptcy” scenario, the economy would be hit on multiple fronts at once. First, you’d likely see a violent recession: credit markets freeze, stock prices collapse, and businesses slash investment.

Unemployment would spike as companies cut jobs, especially in finance, government contractors, and any sector dependent on cheap borrowing. At the same time, the dollar would plunge, because trust in U.S. debt and currency is deeply linked. A weaker dollar makes imports far more expensive—oil, electronics, medicines, all go up in price—so everyday Americans would feel the shock through inflation, even in the middle of a recession (a kind of stagflation).

U.S. government programs that rely on borrowing—defence, social spending, infrastructure—would be forced into emergency cuts or delayed payments, amplifying the downturn.

Losing the ‘World Reserve Standard’

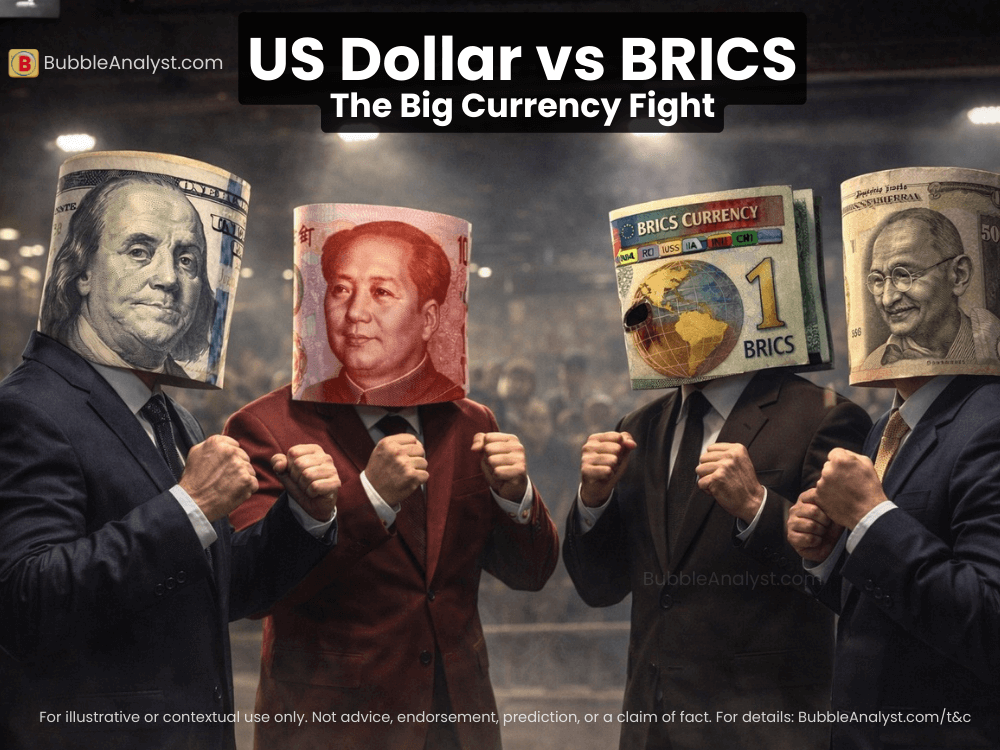

About 60% of global reserves are in U.S. dollars. The euro is about 20%, and everything else — Japanese yen, Chinese yuan, pounds, gold — they all fight over the scraps.

So what happens if that changes?

Well, if there’s a partial shift… for e.g. ‘BRICS’ starts trading oil outside the dollar. The dollar could weaken 5–8%, imports would get around 1% pricier, and Treasury borrowing costs would inch up. It would be annoying, but survivable.

But, if we talk about the absolute extreme – if the whole world abandons the U.S. dollar. If all countries’ central banks dump trillions of dollars of reserves in the market – the dollar could crash up to 50%. U.S. imports could get 5–10% more expensive overnight, interest costs would double, and recession would follow. This is the nightmare situation that the U.S. government is really worried about.

What could be done

The Tough Path

Freeze runaway deficits – Emergency cap on annual borrowing to stop debt from compounding uncontrollably. Defence, subsidies, and discretionary budgets forced under strict fiscal discipline.

Restructure entitlements carefully – Gradual reforms to Social Security, Medicare, and pensions without triggering public revolt.

Rebuild revenue intelligently – Broader tax base, fewer loopholes, targeted indirect taxes over blunt income tax hikes.

The sneaky path

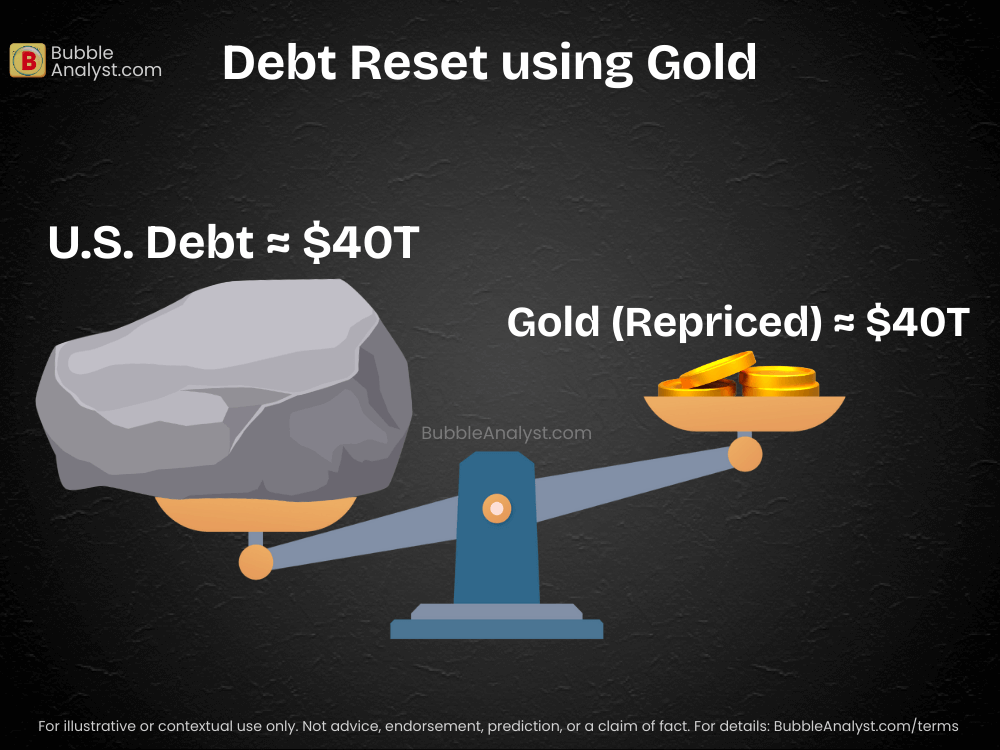

Debt reset through gold – This could involve sharply repricing government gold reserves upward. This would improve sovereign balance sheets on paper, creating the appearance of reduced leverage.

Under a new Bretton Woods–style framework, government-held gold could be revalued significantly higher, making massive debt loads appear more manageable when measured against an expanded gold valuation—without materially changing the underlying debt itself.

Debt reset through Bitcoin (or other crypto) – This is increasingly an open secret. Trump himself hinted at it in an interview, saying the U.S. could “hand them a Bitcoin check.”

Bringing crypto under a federal framework—such as through the GENIUS Act—may be an early move toward controlling how such a reset could be executed. In essence, debt could be shifted into the crypto domain while the dollar remains defended. And if crypto collapses? The blame doesn’t fall on the Treasury or the Fed—only one question remains: where is Satoshi Nakamoto – the founder of bitcoin?

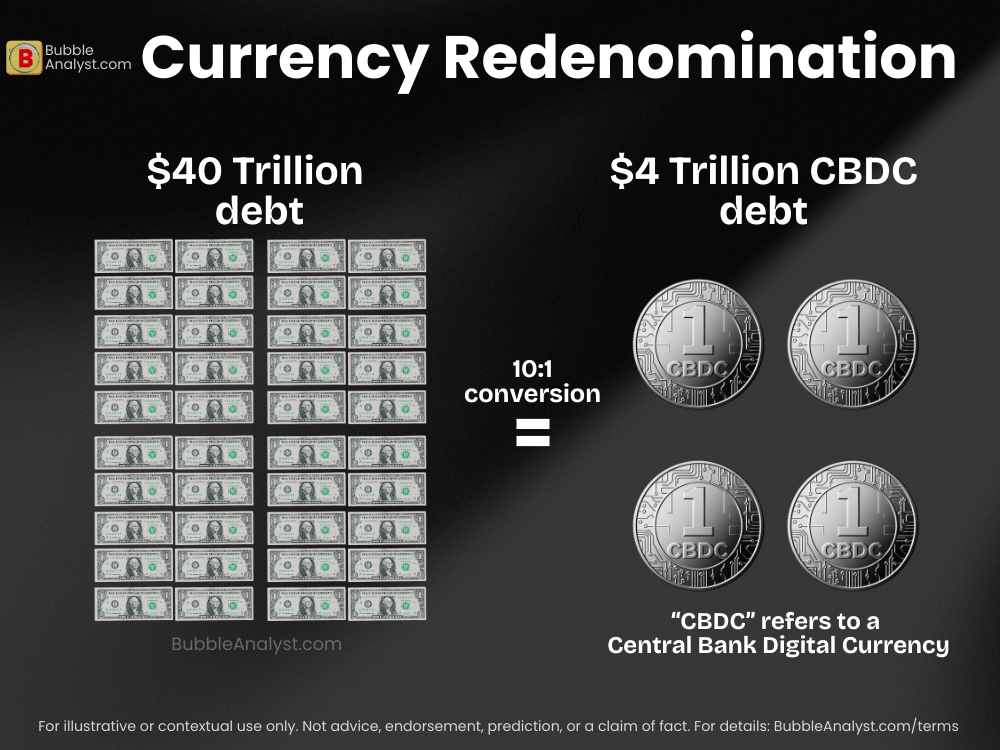

Debt reset through currency redenomination: Currency redenomination is the most blunt debt-reset tool, redefining what each monetary “unit” represents.

It can involve converting multiple old units into one new unit, or shifting domestic debt into a new monetary tier.

A more subtle approach could introduce a “New Dollar” or “Digital Dollar” for domestic use, while external obligations remain unchanged.

Behind the scenes, this compresses the real value of legacy promises while preserving the dollar’s global brand.

Conclusion

The US debt crisis is not a future concern—it is a present imbalance with global consequences. The numbers already rival post–World War II extremes, but without the productivity boom that followed that era. Debt does not disappear; it is either paid, inflated away, restructured, or quietly reassigned.

The “tough path” demands political courage and real sacrifice. The “sneaky path” relies on optics, legal engineering, and narrative control. History suggests governments rarely choose honesty when illusion buys time. At its core, this US government debt crisis will determine who absorbs the losses when the math finally breaks.

Pingback: US Recession in 2026? 5 Hidden Signals Markets Are Ignoring